Why running the ball alone can't win games (and Jamaal Charles is unique)

Examining why "pound the rock" is generally unsustainable, with a side of Charles.

This post is unlocked because it’s the offseason and it’s a good time to read about narrative busting, Chiefs playoff wins, and Jamaal Charles! If you like going beyond the box score and learning about the Chiefs, or football in general, consider subscribing for $12 a year forever by clicking the link below.

One thing I love about the offseason is that the pace is a little slower. What I mean by that is without a game every week to break down, there’s less demand for IMMEDIATE analysis/reaction and a little more time to let things breathe. So when something comes up that grabs my attention, I can play around with it a bit.

This is especially fun when the issue that grabs me is one that relates to general narratives about the game of football. One of the reasons I do this job is to scrutinize various narratives and maxims about the game to see whether they hold truth. The idea is that the more we learn about how the game works, the more there is to love about it (something I’ve found to be true with each new thing I’ve learned about this silly game where the ball isn’t round).

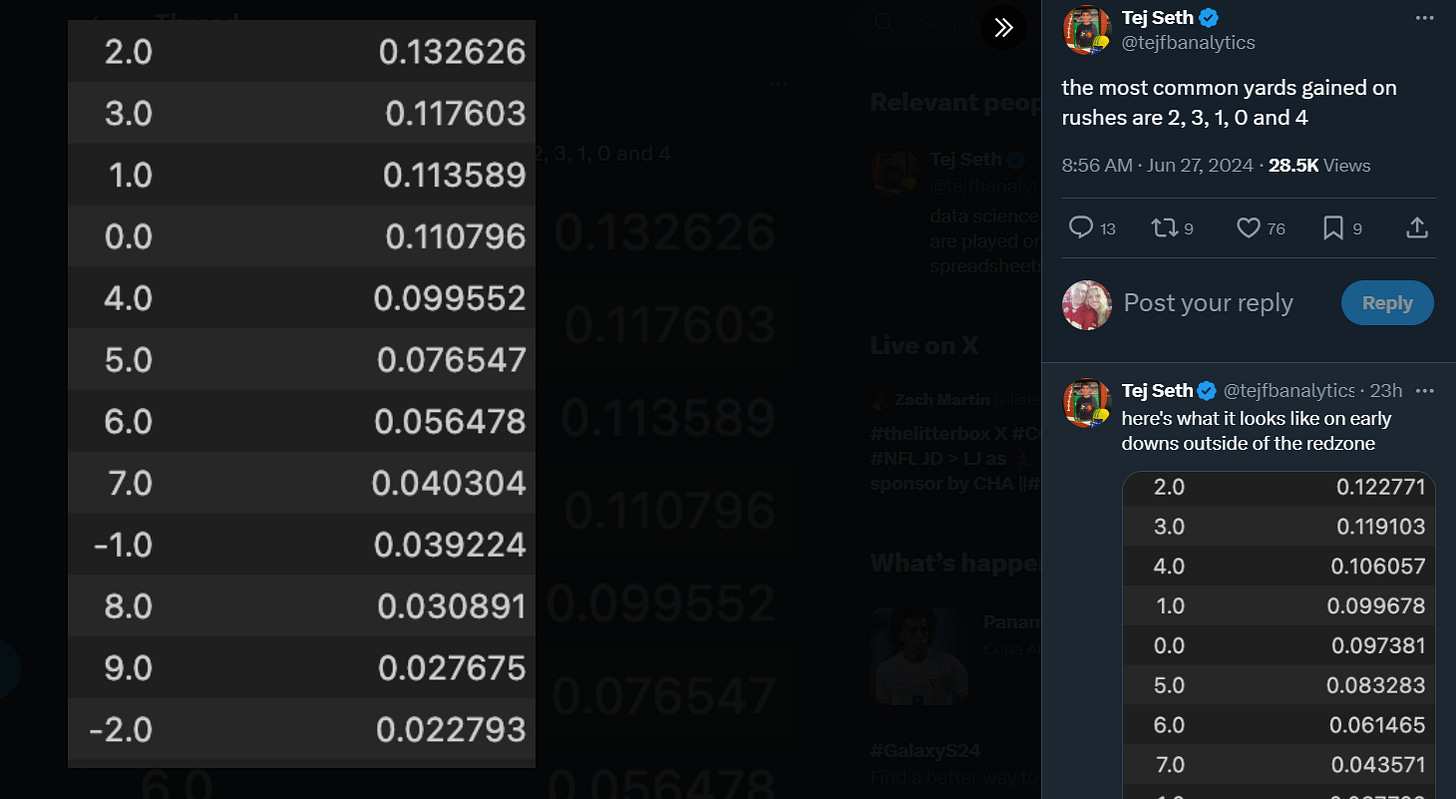

What caught my attention this week were interesting stats related to the run game that were shared by one of my favorite analytics-centric people (and fellow Jamaal Charles stan), Tej Seth (who deserves a follow). I’ll post the numbers in a moment, but the basic idea is that he posted the most common gains when NFL teams run the ball. In other words, rather than looking at an average (which is what yards per carry does), he looked at how often teams gained X number of yards with each run.

The reason this is important is that it relates to the idea of sustainability and basing an offensive attack around the run game. Keep that in mind as we look at the numbers, because I believe it points us towards why the run game can’t be used as a primary weapon in a realistic way. And as a bonus, the Chiefs’ most recent Super Bowl win and playoffs contain multiple examples that demonstrate this idea playing out in real time.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Here are the numbers.

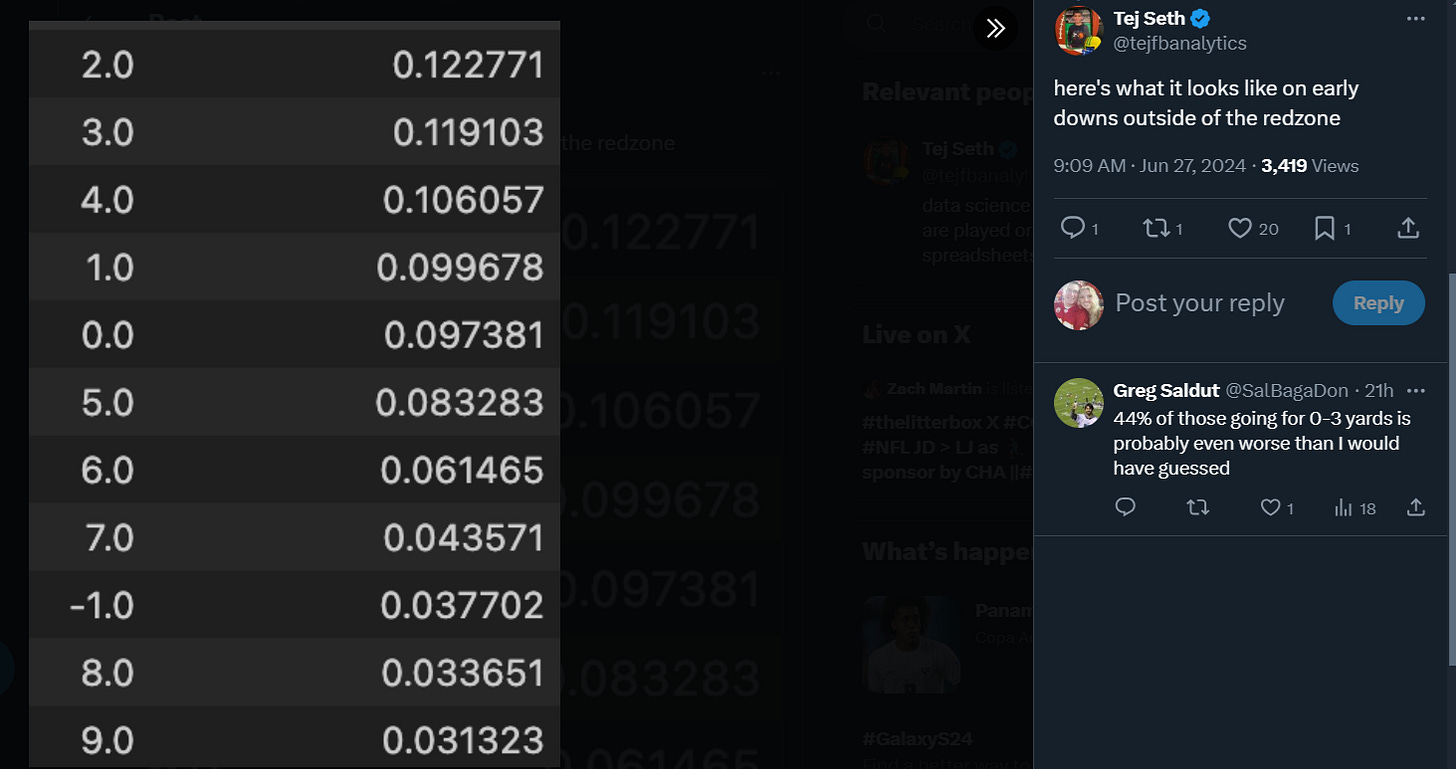

And here are the numbers for when teams are running the ball on early downs outside the red zone (an important distinction).

(again, note that Tej is a terrific follow and deserves all the credit in the world for thinking to lay out the numbers this way).

All right, that’s a lot of information. Why does it matter? Because yards per carry doesn’t capture what NFL games look like in real time, and mislead people into believing that if a team just keeps “hammering away” with the run they’ll eventually matriculate their way down the field.

But football isn’t just a game of averages in real time, it’s a game of downs. In other words, what happens on 1st down affects what happens on 2nd down, and what happens on 2nd down affects 3rd down. And the domino effect can throw an entire series off track. Let’s give a quick and easy example of what I mean by that from the Chiefs’ most recent Super Bowl run (isn’t that fun to say?).

As many know, Steve Spagnuolo’s defense was not considered particularly strong against the run coming into the playoffs. This is pretty common for Spags, as he doesn’t necessarily prioritize stopping the run with consistency in the regular season. However, the narrative heading into the playoffs (as it almost always has been the last few seasons) was that teams should “pound the rock” and punish the Chiefs’ “weak” run defense as a way to keep Patrick Mahomes off the field and shorten games.

That sounds like a great idea in theory. In practice, it’s almost impossible to pull off over the course of a full game due to the numbers above. But again, we’re starting with the example, which happens to come in the very first defensive drive of the playoffs for the Chiefs.

Mahomes and company had marched down the field and scored a touchdown on their first possession against Miami in the Wild Card round, and now the Dolphins’ vaunted offense took the field. It’s worth keeping in mind that while Tua/Hill/Waddle get much of the press, Miami’s varied and exceptionally-well-designed run game is a huge part of their success. Their ability to misdirect defenses often depends on it being a threat. And given the “weakness” of the Chiefs’ run defense, it makes sense that they would start off the game going that route.

But it worked out… poorly. Here’s the first snap of the game for Miami’s offense as they tried to establish the run.

This is a phenomenal rep from the Chiefs defense overall, but it also goes to show how many things have to go right for a run play to succeed (which is true of a pass play as well, but to a lesser degree as it’s more contingent on one player, the QB). Nick Bolton does a terrific job reading the play and hitting the gap, and Willie Gay Jr. forces the FB to make a tough choice by beating his climbing blocker. In the meantime, the guys on the edge set it strong and George Karlaftis pursues well from the back side. The play ends up dead in the water.

Analysis of the play aside, note the result. Miami ends up gaining less than a yard and they now face 2nd and 9. They are now what we call “behind the sticks,” meaning that they’re behind the average yards gained per play that you need to pick up a first down. We’ll talk about what that means for play calling in a moment (because that’s a big part of the numbers issue here). In the meantime, Mike M and company decided to stick with the “pound the rock” plan on 2nd down despite the down and distance. And it went about equally poorly.

This is partly a singular effort play by Gay, who is assigned to basically blow up the left side of the line and does so with his typical ferocity. He knocks back the LT and ruins any chance the RB has of trying to hit the edge. In the meantime, the rest of the line generally holds up, Karlaftis again closes from the back side, and it’s a second consecutive stuff.

And NOW is where we get into a discussion about playcalling. Because two consecutive stuffs mean that the Dolphins are facing 3rd and 8, an obvious passing down and a situation (3rd and long) that places the offense at a significant disadvantage. Anyone bothering to read this understands that when a defense knows the offense HAS to pass the ball, it provides a schematic and play style advantage for the defense due to the limited options available for the offense. Pass rushers can pin their ears back and don’t have to worry about run fits. Linebackers don’t honor play action. Creative blitzes, stunts, twists, and all sorts of games can be run without much fear. And that’s where Spags (and all other good defensive coordinators) generally does his best work.

In case you’re wondering, on that particular drive the Dolphins false-started (in part due to a nice zone blitz look causing an OL to jump) and then failed to convert on a white-flag-waving 3rd and 13 screen. Their failure to gain meaningful yards on 1st down (and then 2nd down) basically killed the drive by putting them in a disadvantageous situation where their play call options were neutered.

All right, now that we’ve utilized a single example, let’s get back to the general numbers from above. Let’s focus on the early down non-red zone numbers in the second list (for purposes of eliminating goal line and 3rd down dives, which would of course naturally shorten runs).

What those numbers tell us is how frequently teams gain certain yardage and lists them (top to bottom) in order of most common. What you can see is that teams most commonly (again, when NOT in the red zone and only on early downs) gain yardage as follows when they run the ball:

2 yards (most common) 12.3% of the time

3 yards 11.9% of the time

4 yards 10.6% of the time

1 yard 10% of the time (rounding up from 9.96)

ZERO yards 9.7% of the time

5 yards 8.3% of the time

6 yards 6.1% of the time (notice the dropoff)

7 yards 4.4% of the time

-1 yards 3.8% of the time

8 yards 3.4% of the time

9 yards 3.1% of the time

Try not to get lost in the weeds with all those different numbers and keep in mind that we’re talking about early downs (so 1st and 2nd down) and thinking about this in terms of how often the run game sets teams behind the sticks. First of all, it’s worth noting that the MOST COMMON GAINS on 1st and 2nd down are 2 yards and then 3 yards. Either of those gains sets an offense theoretically behind the sticks (as the general consensus, right or wrong, is that you want to gain at least 4 yards on 1st down to avoid being placed at a disadvantage).

However, it’s actually worse than just that. Four of the top five numbers there set an offense behind schedule, some of them drastically so. If you add up the numbers you find that on a whopping 43.9% of the snaps teams are getting 3 yards or less when they run the ball on early downs and setting themselves up for limited play calling options (again, this is discounting 3rd and short and red zone runs that naturally shorten the yardage). Perhaps even worse, on over a third of these runs (35.8%) teams are gaining 2 yards or less. You’re substantially more likely, when you run the ball on early downs, to gain 2 yards or less than you are to gain 5 yards or more (25.3% of the plays). It’s not even close, really.

And that’s what brings us back to “football is a game of downs as opposed to averages.” When you run the ball on early downs, on average you are significantly more likely to set yourself up for a bad 2nd down yardage situation than you are to gain 5 yards or more. Which means you’re significantly more likely to handicap your play calling than you are to make a meaningful gain.

(NOTE - Please keep in mind that all of this is situational and none of this is meant to be a “this is for every scenario” argument. If a team is showing 6 guys in the box on 1st down and you’ve got a clear numbers advantage, by all means, run the ball until they stop “cheating” against the pass! This is more discussing a standard course of action and narratives)

And this is why it’s so difficult to sustain an offense based on the ground game. Statistically speaking, you’re going to face situations where running the ball isn’t realistic even if you’re averaging 5 yards per carry, because you’ll still hit that “2, 1, 0, or -1 yards” play too frequently. And then you’re being forced to throw the ball in a bad situation (3rd and long). That’s a tough way to sustain drives. Which means even if, on paper, you’re running the ball well, you’re still setting yourself up for failure if you’re trying to lean on that exclusively.

This newsletter exists solely off reader support. So if you like going beyond the box score and learning more about the Chiefs, click this link to subscribe for $12 a year forever.

A great example of this can be found in the Chiefs’ Divisional Round matchup against the Bills. Buffalo ran for a little over 4.7 yards per carry, a solid number. However, if you look closer on a play by play basis the Bills still put themselves in bad positions on multiple drives when runs did the thing that they eventually do (gain 2 or less yards). It messed with at least three different drives, including two CRUCIAL late-game drives in which big losses in the run game effectively ended drives by setting them up in 3rd and long.

The AFC Championship? Same thing. Baltimore has gotten a lot of bad press for “giving up on the run game,” some of which is warranted. But Spags was using new looks and loaded boxes to essentially DARE the Ravens to pass the ball, and you can see if you look at the play-by-play chart that their 1st, 4th, and 7th drives were all negatively impacted in a major way by runs on early downs that set them behind the sticks.

For example, the first play of the 2nd half the Ravens came out (just like they did to start the game) and tried to get something going on the ground. Instead, they ended up in a bad spot.

I could wax eloquent about terrific run fits from Tranquill, Reid, and Bolton here while Danna held up the edge, but you get the idea. The point here is that the Ravens, down 10 at this point and desperately needing yards, ended up stuffed at the line. They gamely tried to run the ball on 2nd down and were only able to pick up 3 yards. The end result? A 3rd and long in which the Chiefs pass rushers were able to pin their ears back and get pressure while Spags dropped 7 into zone coverage (which meant eyes were on Jackson if he tried to scramble), forcing a near-pick.

The Ravens basically abandoned the run overall after this, and frankly it’s hard to blame them when half of their meaningful drives to that point (three out of six, as one of their 7 drives was an end-of-half drive that didn’t really do anything) had been actively hurt by the run game setting them behind the sticks. Situationally, the run was hurting them.

Again, it’s not about averaging a certain yardage per carry. At least, it’s not JUST about that. It’s about not putting yourself in situations where running the ball isn’t realistic and you’re giving the defense an advantage. The ironic thing about running the ball a lot (as the numbers bear out) is that by doing so you OFTEN put yourself in a situation where running the ball isn’t realistic. And then you have to throw the ball well with your back against the wall on 3rd and long.

Still not convinced after examples from 3 consecutive playoff games against opponents who run the ball well? Well, let’s look at the Super Bowl! The vaunted 49ers rushing attack was supposed to be a big mismatch against Spags and company. Now it’s worth noting that terrific performances from role players like Leo Chenal, Tershawn Wharton and Mike Pennel helped make sure that didn’t play out. But all the same, it’s interesting to look at the number of drives that the Niners ended up behind the sticks due to runs of 2 yards or less. It’s six total if you examine the play-by-play chart, including their “held to field goal” drives late in the 4th and overtime.

All this is a long road to a short thought… the run game, while valuable selectively and depending on matchup/personnel/scheme, generally does not show the ability to sustain drives because by its very nature it has too many “sets you behind the sticks” plays without the commensurate number of “big plays” to make up for it. And because of that, saying a team can win games consistently with the run game (without a good passing game to convert on those longer down and distances) is just wrong.

So the next time someone tells you that a team is going to win a game with their rushing attack, just know that while it COULD happen in theory, the reality is even a strong rushing attack isn’t enough to sustain drives the vast majority of the time. And it’s all because football is a game of downs.

But Seth, what does this have to do with Jamaal Charles?

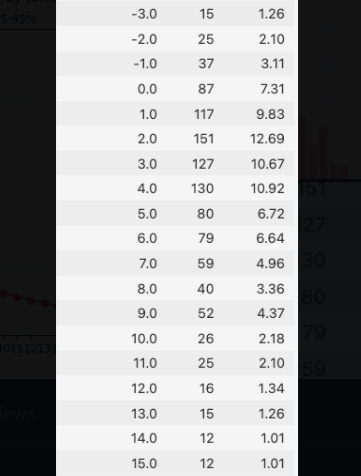

I’m so glad you asked! Thanks to my former colleague and Good Dude Ethan Douglas, we also have Charles’ numbers broken down in a “how often did he gain X number of yards” format! He did it multiple ways (because he’s a good dude), but here’s the list that most closely matches how we’ve looked at other RB numbers…

(NOTE- Ethan did isolate for win probability between 5-95 percent to eliminate garbage time, but he did NOT isolate away red zone carries, meaning we need to compare his numbers to the first screenshot of the NFL at large for comparison purposes, not the second. I’ve also left out stuff under 1%)

One thing to note here that actually go towards the overall point that you cannot JUST run the ball. Even Charles, an incredible runner, was still almost as likely to gain 3 yards or less (46.97%) as not when he carried he ball. In other words, even with an all-time terrific runner, you’re still in a spot that you can’t consistently move the ball that way throughout the course of a game.

However, Charles definitely distinguishes himself from other RB’s in several big ways. Again, keep in mind that these numbers (unlike the ones we used to discuss the general issue with running the ball as a primary driver of the offense) are NOT isolated from red zone carries and early downs, and so are going to be slightly different. But Charles shows how unique he is in two major ways.

First, while his likelihood of gaining 3 yards or fewer is 46.97%, that’s markedly lower than the NFL average. That number is 53.76%. And so Charles is less likely by a fair margin to set you behind the sticks when he carries the ball than what the NFL average would be.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, Charles is SUBSTANTIALLY more likely to place an offense well ahead of the sticks than normal. The NFL as a whole gained 5 or more yards on 23.1% of their carries. Charles did so 34.95% of the time! And so over a third of the time when he ran the ball, Charles was getting the offense ahead of schedule and putting them in advantageous positions.

In short, Jamaal Charles’ case for being unique (and Hall of Fame worthy) is enhanced by looking at these in-depth numbers, just like it is when looking at other advanced numbers. He’s markedly less likely to set the offense behind than a normal running back, and substantially more likely to put the offense ahead. And all of this without ever having the benefit of an elite line (and many years having a flat-out bad passing game). In other words, Charles is great. But I’m guessing you already knew that if you watched him play. I just couldn’t miss he chance to talk about how unique a player Jamaal Charles is.

The overall takeaway, though? It’s pretty simple… While the run game will always be important for schematic purposes and to keep defenses honest against the pass, it is NOT a safe bet to sustain offense over the course of an entire game (let alone an entire season). There are too many snaps where it sets the offense behind the sticks for it to work that way when you stop looking at averages and start looking at things on a snap by snap basis. The numbers and the specific examples bear it out.

So next time someone says an opponent will hammer Spags’ defense into submission with the run game, just smile and know that the vast majority of the time that won’t be how it works out. Just ask the Dolphins. Or the Bills. Or the Ravens. Or even the 49ers.

"So next time someone says an opponent will hammer Spags’ defense into submission with the run game, just smile and know that the vast majority of the time that won’t be how it works out."

It's good advice to just smile, because I find that most fans do not like having their conventional wisdom challenged.

Thanks for the interesting article, Seth. I can't count the number of times I've fantasized about Mahomes in shotgun and Jamal Charles motioning out of the backfield and setting up in trips with Kelcie and Tyreek.... then my alarm wakes me up